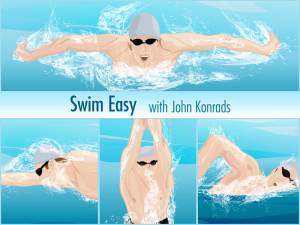

John Konrads holds 26 individual world records and won the 1500 m freestyle in the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome. He now coaches up in the beautiful Sunshine Coast in Queensland. One of his mantras is “swim easy”.

In this podcast episode I will talk to John and see how we can prove how swimming can be “effortless” and easy”.

Brenton: Welcome to the Effortless Swimming podcast. My guest today is John Konrads, who you’ve probably heard of. He won the 1500 m freestyle in the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome and in his career he’s set 26 individual world records. He now coaches up in the beautiful Sunshine Coast in Queensland. I’ve got John here on the call today. We’re going to talk about a few things about technique so you can swim easier, swim more efficiently and improve your swimming. So welcome to the call, John.

Brenton: Thanks, John. One of your mantras is “swim easy”. You’ve got a book and DVD titled Swim Easy. I think that fits in really well with “Effortless Swimming” which is my mantra and I guess one of the common things that comes up is that some people say that swimming’s not easy, swimming’s not effortless. But, I think the way that we speak about it it’s about using energy in the right places and conserving energy in the right places.

John Konrads: Absolutely, but let’s take a big step backwards. Humans aren’t built for swimming. You know, you put a little puppy dog in the water and it automatically swims. That’s not so with a child. In the recent floods I saw videos on the news of kangaroos swimming. Human beings aren’t built to swim and, therefore, it’s a foreign environment and we were taught when we were toddlers that it’s a dangerous environment. So this sets up tension and anxiety. One of the key things is that everyone has a bit of anxiety. Grant Hackett on the last lap of the 1500 when he’s buggered doesn’t let a drop of water down his throat from a passing swimmer – be going the other way, I hope – or off the tip of his fingertips and have to cough. Have you ever coughed at the end of a 1500 or got a mouth full of water? It is not fun. So we’ve got this tension built in and the key thing to that is first to recognise it and secondly work against it, or work to overcome it. And the thing I use now in all my swim clinics – and I have to give credit to Milton Nelms who you may’ve heard of. Milt’s a fantastic guy; he used to work with the US Olympic team and he a couple of years ago married Shane Gould so he’s become an Aussie living in Tasmania I think. But what we call the hang float – just float completely loosely in the water like a piece of seaweed or a piece of jellyfish, face down, arms and legs dangling down depending on body density, and even good swimmers find this confronting. They’re not used to being perfectly relaxed in the water. The Red Cross call it the dead man’s float. And that’s the way of telling your “fight-flight” brain, your permanent brain, “Hey, this is ok.” And what I find interestingly surprising, particularly triathletes because they’re bikers and runners 90% of the time – they’re just not used to doing it. Biking is natural to human beings – it’s a running type movement done on a machine but swimming sure isn’t; it’s a different world all together.

Brenton: Absolutely, and you can tell the difference between a swimmer that is relaxed in the water and one that’s not just by looking at their stroke – their distance per stroke – as well. I used to coach down at the Melbourne University pool probably about five or six years ago and the pool is only about 1 m 70 cm – maybe 1 m 60 cm – deep and they’d get a lot of foreign exchange students who had never learnt to swim who would go there and they’d need to be rescued in the water because of what you’re talking about. They go into that flight mode and they panic and they become anxious and they struggle to float or swim in that depth of water.

John Konrads: Yeah, and the other thing is that subconscious drive – it’s part of the fight-flight brain. It’s completely involuntary. It drives us upwards – it’s warm up there, it’s cold down there; sharks are down there, salvation’s up there. So we want to angle upwards and swim what I call the water-ski complex – if I slow down I’ll sink. And I want to get people to sink at floatation depth. And this is particularly true, once again, for athletes because they have very little – if any – body fat. So they’re not good floaters, so for those guys and girls, all the more reason to swim low in the water and to breathe, particularly to, in recovery, rotate more. You do real slow-mo shots of Thorpe or Hackett coming toward you. They’re rotating through 180 degrees; their shoulder points are vertical. I often say things like two side strokes put together; their shoulder points are vertical in recovery; in other words, one shoulder is directly above the other. So people with high body density, the sinkers so to speak, have to rotate more to breath looking skywards. Kieren Perkins used to look up at the ceiling – up at the sky – when he breathed. Took his goggles out of the water looking skywards. That means he’s not lifting, the water’s doing the work of holding him up, he can concentrate his energy on going forwards.

Brenton: And that kind of ties in as well to something that you’ve probably come across when you’re doing one on one lessons or you’re doing private group classes and that’s swimmers that tend to hold their breath when they’re swimming freestyle so when their face is in the water they’re not breathing out constantly. Can you talk a little bit about what kind of impact that has on their stroke and on their energy levels as well?

John Konrads: Breathing is the most important thing we do, which causes problems in swimming because you know, if you come across a car accident and you’ve got some first aid knowledge the first thing you do is check the breathing; there’s no use saving somebody who’s bleeding if they’re not breathing. And I’m being particularly sinister about this because it’s so powerful all these emotions that we have. Since breathing’s the most important thing we do, the source of all evil comes from breathing, or most evil anyway because we want to get a good breath, therefore we tend to lift to breathe, for example, or we don’t breathe out enough. Try emptying your lungs until they’re completely empty all the way down to the bottom, and then cough. In other words you’ve still got enough air left in your lungs to cough even if you think your lungs are empty. And I focus on exhaling because if people exhale they’ll sure as hell inhale again. If they inhale, they may not exhale. So the key to breathing is focus on exhale, and don’t lift to breathe, roll to breathe.

Brenton: What I recommend to swimmers who are having trouble with their breathing is that, take your breath and when your face goes under the water you’re just constantly releasing air from your lungs whether through your nose or through your mouth or through both and then just before you take that breath.

John Konrads: Through both.

Brenton: Through both and then release all of the oxygen or all the air just before you take that breath so that you’ve got empty lungs in order to take a full breath.

John Konrads: And it clears the passage ways too. Think of a whale surfacing – it clears the passageways with a big blast and then breathes in immediately afterwards. In fact, I was looking at some David Attenborough thing just recently that was showing overhead pictures of the whales and the spout lasts a couple of seconds and then you see the gap open up but the whale inhales in about less than a second. I was very surprised actually I thought these guys have got such huge lungs they’d take longer to inhale but it doesn’t take long at all to inhale. And the spout to exhale takes much longer – plus everything else they’ve got to spill the water out – it’s interesting stuff. The other thing particularly with, once again, triathletes is that air resistance is their enemy – wind; it’s great to have a bike in front of you to break the air. But water resistance I think is the same thing. Water is your friend because you’re using it to propel yourself. The key thing to remember in swimming is that water resistance is a question of streamlining first of all to reduce the water resistance. But the key thing here is that a submarine goes faster than a surface ship with the same power and weight. It’s because a submarine doesn’t waste energy breaking the surface. Sure there are waves under water but it creates more waves at the surface than it does under water. So the surface is the most inefficient place to propel yourself. So stay low and think torpedo rather than speedboat. So don’t try to fight water resistance by aqua-planing up – all you’re doing is wasting energy.

Brenton: One of your main principles when you’re teaching swimming is swimming at flotation depth which is what you’re sort of talking about there.

John Konrads: The objective is to let the water do all the work and that means you’re swimming on a straight axis from the crown of your head out your bum between your legs and so your spine is as close as possible parallel to the water surface and your axis on which you rotate like a barbecue roast – a spit roast – that’s parallel to the surface of the water.

Brenton: You might find the same thing when you’re taking people through some technique work, one of the main things that I come across is that swimmers will either be kicking too hard or they’ll be bending at their hips so that their legs are dragging below them which is causing quite a bit of resistance. So they’re two of the main things we start with that we’re working on. What do you find in terms of how hard someone’s kicking to how tired they get in the water?

John Konrads: The thing is that when we learn to swim as kids, we learn to kick first and then we learn to kick hard and our teachers, “Kick hard Johnny. Kick hard Jenny.” So in our brain – in our subconscious – is the fact that kicking is good. But kicking is the most inefficient thing we do because we try to make fish tails out of our feet and they’re not built like fish tails. Flippers make fish tails out of our feet; that’s how they get so much propulsion. But kicking is just inefficient. Everybody hates kicking on a kickboard, and rightfully so, because it’s bloody frustrating hard work. But when you’re swimming it’s no less easy. What I say is that the reluctant kick is not worth the effort. When Thorpe does pull buoy, and he’s got the fastest kick in the world along with Alex Popov, what is it 28.6 for 50 m kicking with a push off. I was standing next to him one day when I heard it. I know him pretty well and said, “I heard you did 28.6 for 50 m kicking.” I said, “That was with a dive and an underwater dolphin, wasn’t it?” He looked down at me and said, “No, that was with a push off and a kickboard.” Even I get a bit nervous in his presence so I should’ve kept my mouth shut until I heard his answer. But when he does pull buoy he goes 10 percent slower. I’ve seen him do a set of 30 100s 15 with swimming, leaving on the 65 and holding 59 and without resting, he grabs a pull buoy and he’s leaving on 70 holding 64 or 65 with a pull buoy. He is the greatest kicker in the world. So, kicking is not worth the effort, particularly in triathletes who have to use their legs afterwards. I’m a triathlete coach but a former triathlete coach once said that when a triathlete gets out of the swimming leg their heartbeat should be around about 130 or 140 and that’s the key thing: swimming is the odd man out in a triathlon.

Brenton: I like to teach for them to kick but not use effort in the kick. It’s really important for balance and timing and I see too many triathletes in particular trying a two beat kick which I don’t think works for a lot of swimmers mostly just because they can’t use the drive from their body rotation quite as much because they’re just working too hard on their pull so I think a four or six beat kick is usually a better option for most swimmers and I think too many swimmers try and do a two beat kick but it’s just a bit too slow where they could be quicker.

John Konrads: You know the rhythm of the kick I leave it up to the swimmer. First of all, I’m talking about most of my customers are middle of the road lap swimmers not master swimmers, people who just want to swim a kilometre for a workout or maybe go in the odd beach race and to talk about six beat or two beats that takes the focus off their arms and starts concentrating on the legs, but the legs are involved in body rotation as well as the arms so I sort of leave it up to them – let your legs do what they want to do so long as you’re not kicking too hard and let them find their own speed of beat. The other thing about kicking of course is that you’re engaging your quadriceps which are the largest muscles in your body so using your largest muscles in your body to produce the most inefficient movement which is kicking.

John Konrads: Well the rubber on the road is the pull phase of the stroke. In the catch, the only downward pressure that’s required is to offset the weight of the opposite arm which is then in the air. So all of a sudden you’ve got between four and six kilos going upwards in your recovering arm and so that doesn’t push you downwards, the catch is a downwards pressure to offset that, but then when the catch turns into the pull which is forward of the head and I could talk about catch up and delay pulling in, but that’s the rubber on the road; that’s where all the action takes place. The push at the end of the stroke – there’s quite a different set of ideas from different people as to whether it’s a waste of energy or should you finish with a good push or just let your arm finish the stroke. That depends, I think, on the strength of the triceps of the person and other things like that. But the key to the speed and pull action is the pull. One is their innate sense of streamlining – they streamline beautifully, they can feel that they’re streamlined intuitively. And the second one is the quality of their grip on the water – the rubber on the road. One of the most remarkable swimmers of the last decade and a bit is Natalie Coughlin from the USA who happens to be a Milton Nelms protégée in terms of stroke mechanics and in terms of coaching. And Libby is 5′ 7″ – sorry about the old language but I’m an oldie – with size 7 feet; Natalie is 5′ 8″ with size 7 feet and reputedly the weakest member of the US Olympic Team. First swimmer in the world for under a minute for 100 m backstroke. The thing about streamlining – both Libby and Natalie come out a metre ahead out of tumble turns, that’s so noticeable in freestyle because Natalie got the bronze in the 100 m freestyle twice too. And secondly, just the quality of their grip on the water, and they’ve got small hands. It’s a feeling thing. And that’s why I like drills which are like swimming close-fisted intentionally then open your hands up to feel the satisfaction of your grip on the water, swim with your fingers spread apart intentionally and do the same and develop a feel for the water. This is the rubber on the road – Michael Schumacher can go a tenth of a second faster than Rubens Barrichello in the same Ferrari, it’s seat of the pants stuff; they’re the two big issues and as I said, the pull is the rubber on the road.

Brenton: One of the things I’ve been working with my squad with lately is just getting the streamline right off the start and off each turn because I’d say probably nine out of ten of just my squad alone which is an adult squad is they’ll push off and their streamline is not good at all – their hands aren’t together, they’re not locking in their elbows, they’re just pushing off and they almost hit a wall when they push off so we’ve been working a lot just on that kind of streamline and that also helps to get a feel for streamlining your stroke. And with coaching adults, they might not have the best flexibility as some of the kids but you can work on that and it’s not going to be a comfortable position when you do push off the wall in a streamlined position but the more you can do it the better you’ll get and then the better you’ll be able to apply that to your stroke.

John Konrads: What I like is pushing off the wall and not kicking or moving and seeing how far you can push off just holding your breath and waiting until your body stops. And obviously, the more streamlined you are the further you’ll go with practice, or with a dive even you can do the same thing. Usually the head gets in the way in streamlining if people start lifting their head too early and the same with swimming. The fact is, for years in the 90s when I first started getting back into coaching because I was in the business world for 30 odd years, I still recommended looking forward under the water because it’s natural for a human being to see where they’re going and it took me to tell me, “John, things have changed since your day.” And the objective is not looking down, the objective is to streamline and not use your upper neck muscles because those muscles use a hell of a lot of energy – they’re the twitchy work muscles to swing your head around in emergencies. So, the head is the key thing and just practicing by pushing off or diving without moving and seeing how far you can get.

Brenton: I just want to talk about one more thing and that’s over exaggerating a movement in a drill or in the water to help get a feel for it or to help to learn that thing. I know it’s one of the things you mention in your DVD and it’s something I like to do as well particularly with drills to over emphasize something. So, for example, if a swimmer is bending their knees too much when they kick so it’s like they’re riding a bicycle, I’ll get them to kick just by keeping their legs straight and so we’re over exaggerating the straightness of the legs to help them get the feel for what they should be doing. You do a bit of that too, don’t you?

John Konrads: Yeah, and nobody’s been able to explain to me why but in swimming a little bit of change feels like a lot. Somebody who’s crossing over in their entry, crossing over to the other side; to get them to stop doing that they think that their arms are going out wider than their shoulders. So learning by exaggeration is good. And I do want to focus on catch up or the way they pull because I think that’s the second biggest thing. I still like the old catch up drill. I’ve tried every single drill I can lay my hands on but I call it thumb touch because catch up suggests rushing. Take a stroke touch your thumbs in front, take the other stroke, and touch your thumbs in front. And this teaches you the catch up if you like; it’s an old-fashioned word. The catch up is critical because if you start pulling too soon, in other words your arms are rotating faster; your pull is out of sync with your body rotation. If you delay the pull until the opposite hand enters, that means you’ve got momentarily two hands forward of your head, you have the longest combination of body rotation and pull which is using your body weight to add power to your arm pull. You name it, boxing, golf, tennis; think about Layton Hewitt hitting a backhand without rotation, the ball wouldn’t even reach the net. So you’ve got this delayed pull. I call it delayed pull rather than catch up – same thing. And this reduces the number of strokes per lap because each stroke is more powerful with the same energy and it takes you further. And I was really interested in this new 16 year old kid, Jordan Harrison, I only saw him on the news. I’d love to see some footage of him; I’ll go down and see him in Southport at Denis Cotterell’s and see. He’s hands get to within about 18 inches of each other in front. That means my guess is that he’s doing about 30 strokes per 50, maybe even less. The only person whose done under 30 is Thorpe in his 200 m world record in laps 2 and 3 in Japan in 2003 – his stroke count was 29 for laps 2 and 3. He used to stroke 34 when he first broke world records. Grant was stroking 35 when he first started breaking world records and his last world record was 31 strokes per lap. Don’t confuse arm speed with swimming speed. If you’re pulling too soon, you’re driving in second gear. You’ve got more revs and using more fuel but you’re not going faster.

Brenton: Yeah, that’s right. And you see it a lot when you’re maybe taking football players or rugby players where you are and they’ve got a lot of power – a lot of strength – and they’ll try and use that to try and pull themselves through the water really quickly by really rushing their hands through the water. But swimming’s not really about that; it’s about holding the water and then moving yourself past your hand and getting a good grip on it so to speak.

John Konrads: Yeah, I’ve got first-hand experience of that. When I had the lease of the Cook + Phillip Park, the South Sydney Rabbitohs came to the recovery sessions and some of the boys didn’t swim too well because they grew up with a rugby ball in their hands. And particularly the Islander boys, they didn’t like the water because they sank all the time because they’re built like brick outhouses and they float like brick outhouses and when they pull they rip a hole in the water. It’s a little bit like wheel-spin in a powerful car, you don’t go forwards. I use a lot of analogies outside of swimming which I think is a good way of picturing things. And they couldn’t float either. And getting back to what we started on, the hang float or the seaweed float, when you’re relaxed your body expands in volume and people who consider themselves as sinkers, and there are plenty of those in the triathlon world, with relaxation their body expands in volume for the same weight, so slowly, they’ll either get their back up to the surface or even their legs will start coming up higher in a hang float so there’s a lot to it.

Brenton: Yeah, a lot of things to think about. No matter how good you get as a swimmer, there’s always something to work on – something to concentrate on – but I think that’s part of the enjoyment that comes with swimming is just consistently improving and working on different things. John, thank you so much for jumping on the podcast with me. I really appreciate you sharing your experience and your knowledge on here. How can people find out more about you, about the DVDs you offer, and also if they would like private or group lessons with you?

John Konrads: I’m on the web, JohnKonrads.com.au – johnkonrads one word with a k and s on the end. And it’s John, not Jon like some people dub me because of Jon Hendricks. But most of your customers will say John Who? Because I was talking to a bunch of my kids one day at the squad in Cook and Phillip Park. They were about 8 and 9 years old and I said, “Who’s your favourite swimmer?” And they said, “Oh, Grant Hackett, and Libby Trickett” (or Libby Lenton in those days) and I said, “What about Kieren Perkins?” And there was silence. And then one kid pipes up and says, “Oh, he’s real old, isn’t he?” So that’s kids for you.

Brenton: I think most of my customers; they’re in the 30-50 year age group so I’m sure most of them have heard of you. It’s been great to have you on the podcast John, thanks so much. So JohnKonrads.com.au to get more information about John and if you’d like to get any of his books or DVDs or organise any private lessons with him. So thanks again John, I really appreciate it.

John Konrads: Good on you Brenton. Thank you.